Dear Reader,

Welcome back to the final segment of my Scooby-Doo analysis! (Part 1, Part 2) Today, I am focusing extensively on Scooby-Doo, Mystery Incorporated, the second to most recent incarnation of the franchise. As much as I would love to go episode by episode to pick out all the references and the little moments that make me love this show, we must settle for a very thorough overview – its structure, innovation, and where it lies in the context of children’s animated television programming as well as the franchise’s enduring and evolving legacy. Please enjoy!

Developed by Mitch Watson, Spike Brant and Tony Cervone, Mystery Incorporated aired on Cartoon Network, through the Turner Broadcasting Company division of Time-Warner, and is the first Scooby-Doo show to air during the week (Monday), rather than part of the typical Saturday morning cartoon lineup.

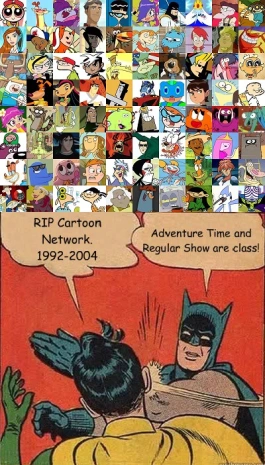

Since Cartoon Network’s launch in 1992, the network has provided a string of mature, children’s content that balances darker tones and themes, supernatural and otherwise non-realistic elements, and kid’s humor, elevating overall the standard for children’s televised content. In fantasy, they have Adventure Time (2010-8); in science fiction, Ben 10: Alien Force (2008-10) and Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008-14); and in the superhero realm, their cup ran over with plenty: Batman: The Animated Series (1992-1995), Justice League (2001-4), Justice League Unlimited (2004-6), Teen Titans (2003-6), and the newly-revived Young Justice (2010-3, present). For straight comedy as well as in the action and supernatural genres, Cartoon Network developed, respectively, Ed, Edd n Eddy (1999-2008), Samurai Jack (2001-4) and Codename: Kid’s Next Door (2002-8), and The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy (2003-8). With Scooby-Doo, the trend continues.

Since Cartoon Network’s launch in 1992, the network has provided a string of mature, children’s content that balances darker tones and themes, supernatural and otherwise non-realistic elements, and kid’s humor, elevating overall the standard for children’s televised content. In fantasy, they have Adventure Time (2010-8); in science fiction, Ben 10: Alien Force (2008-10) and Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008-14); and in the superhero realm, their cup ran over with plenty: Batman: The Animated Series (1992-1995), Justice League (2001-4), Justice League Unlimited (2004-6), Teen Titans (2003-6), and the newly-revived Young Justice (2010-3, present). For straight comedy as well as in the action and supernatural genres, Cartoon Network developed, respectively, Ed, Edd n Eddy (1999-2008), Samurai Jack (2001-4) and Codename: Kid’s Next Door (2002-8), and The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy (2003-8). With Scooby-Doo, the trend continues.

Three innovations of Mystery Incorporated are its inclusion of an overarching plot, inter-character drama, and an essential skeleton of supernatural and magic-based mysteries. The basic Scooby foundation remains the same – new mystery each episode with a man-in-mask villain – however, the villains are more creatively conceived and there is a pervading threat through both seasons. Furthermore, each member of the gang is given equal screen time, motivation, characterization, and backstory (including but not limited to, an age, parents, a hometown, and personalities). The show, although set in the present (with cellphones and laptops), possesses the aesthetic of the 1970s show in attire and design, but with the sound and musical style of classic 1980s cinema (complete with John Carpenter- or Tangerine Dream-style synth).

Set in the West Coast town of Crystal Cove, the self-identified “Most Hauntedest Place on Earth,” the gang goes to school, sorts out their relationships and friendships, negotiates parental expectations, and most importantly, searches for and solves mysteries. For example, a storyline in the first season involves the failed, mostly clandestine relationship of Velma and Shaggy (who was unwilling to confess this to Scooby), which majorly affected the group dynamics and their ability to work together. In both seasons, the constant conflict remains between Daphne, who is hopelessly in love with Fred, and Fred, who friend zones her because he is incapable of expressing his emotions (due to his love-hate, repressive relationship with his “father”). Unlike the original run, Mystery Incorporated does not shy away from romantic relationships, sexual or sensual expression, and implicit sexuality. When in a relationship, Fred and Daphne as well as Shaggy and Velma go on dates, kiss, and meet each other’s parents; and after difficult break-ups, have rebound relationships. Daphne regularly wears a nearly-sheer negligee, once wore a bikini to get Fred’s attention, and even accepts his marriage proposal at the end of the first season; while Velma implicitly engages in a lesbian relationship with rival-turned-partner Marcy “Hot Dog Water” Fleach.

Set in the West Coast town of Crystal Cove, the self-identified “Most Hauntedest Place on Earth,” the gang goes to school, sorts out their relationships and friendships, negotiates parental expectations, and most importantly, searches for and solves mysteries. For example, a storyline in the first season involves the failed, mostly clandestine relationship of Velma and Shaggy (who was unwilling to confess this to Scooby), which majorly affected the group dynamics and their ability to work together. In both seasons, the constant conflict remains between Daphne, who is hopelessly in love with Fred, and Fred, who friend zones her because he is incapable of expressing his emotions (due to his love-hate, repressive relationship with his “father”). Unlike the original run, Mystery Incorporated does not shy away from romantic relationships, sexual or sensual expression, and implicit sexuality. When in a relationship, Fred and Daphne as well as Shaggy and Velma go on dates, kiss, and meet each other’s parents; and after difficult break-ups, have rebound relationships. Daphne regularly wears a nearly-sheer negligee, once wore a bikini to get Fred’s attention, and even accepts his marriage proposal at the end of the first season; while Velma implicitly engages in a lesbian relationship with rival-turned-partner Marcy “Hot Dog Water” Fleach.

Two episodes in the second season provide examples: In “Grim Judgment (S2E9), a villain dressed as a Puritan judge named Hebediah Grim attacks the town’s teens on Lovers’ Lane, judging them (particularly the women) for their impurity. While investigating, the gang is interrupted by two youths parked at the lane who exclaim: “Hey, how are we supposed to make incredibly bad and stupid decisions that will wreck and ruin the rest of our lives over here with all that noise?” This one line can be read as allusions to teenage sexuality, promiscuity, and teen pregnancy. In the next episode, “Night Terrors,” which takes the frame of the “That Snow Ghost” episode from the original show (S2E17), but fills it with visual and narrative cues to The Shining (1980). Trapped by a snowstorm and avalanche in the isolated Burlington Library, the gang is exposed to the fictitious “terror wood” which causes hallucinations, such as when Daphne hallucinates that Shaggy is Freddy and Shaggy too hallucinates that he is the muscular, hyper-masculine Fred. The two engage in kissing (and whatever else may be inferred) before the gang finds them and exposes the fantasy.

Two episodes in the second season provide examples: In “Grim Judgment (S2E9), a villain dressed as a Puritan judge named Hebediah Grim attacks the town’s teens on Lovers’ Lane, judging them (particularly the women) for their impurity. While investigating, the gang is interrupted by two youths parked at the lane who exclaim: “Hey, how are we supposed to make incredibly bad and stupid decisions that will wreck and ruin the rest of our lives over here with all that noise?” This one line can be read as allusions to teenage sexuality, promiscuity, and teen pregnancy. In the next episode, “Night Terrors,” which takes the frame of the “That Snow Ghost” episode from the original show (S2E17), but fills it with visual and narrative cues to The Shining (1980). Trapped by a snowstorm and avalanche in the isolated Burlington Library, the gang is exposed to the fictitious “terror wood” which causes hallucinations, such as when Daphne hallucinates that Shaggy is Freddy and Shaggy too hallucinates that he is the muscular, hyper-masculine Fred. The two engage in kissing (and whatever else may be inferred) before the gang finds them and exposes the fantasy.

Moreover, Mystery Incorporated raises the narrative and character stakes by injecting violence and death into the show, this time with consequences and not for comedic purposes. In the original founding of Crystal Cove, Spanish conquistadors (inspired by Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God [1972]) are driven insane by an “Evil Entity” to commit colonial atrocities – pillaging, murdering, and scorching the nearby Mayan natives. Also influenced by this entity, a mystery group’s mascot (a donkey) sets off explosives which sunk most of the first Crystal Cove settlement and half its population into the Pacific Ocean. Centuries later, a mystery-solving family was killed when their mansion was consumed by the earth, from which the “entity” influenced the younger son to hide from his family, as they all died and wasted away into dust.

Moreover, Mystery Incorporated raises the narrative and character stakes by injecting violence and death into the show, this time with consequences and not for comedic purposes. In the original founding of Crystal Cove, Spanish conquistadors (inspired by Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God [1972]) are driven insane by an “Evil Entity” to commit colonial atrocities – pillaging, murdering, and scorching the nearby Mayan natives. Also influenced by this entity, a mystery group’s mascot (a donkey) sets off explosives which sunk most of the first Crystal Cove settlement and half its population into the Pacific Ocean. Centuries later, a mystery-solving family was killed when their mansion was consumed by the earth, from which the “entity” influenced the younger son to hide from his family, as they all died and wasted away into dust.

The bulk of the supernatural violence occurs in the second season, however, some victims of the man-in-mask capers do die (consumed by Cicada bugs or mauled to death offscreen by a parrot). Even Scooby’s girlfriend, Nova, is rendered comatose (then dies) in a Mufasa-inspired stampede scene. The exponentially-raised stakes require each episode to start with a recap, unheard of in the preceding incarnations, furthermore, it creates a tighter, more compelling narrative. In the second season, beloved characters like Angel Dynamite (inspired by Pam Grier and Blaxploitation heroines) sacrifices herself to save the gang, and drowns, while “Hot Dog Water” distracts the series’ villain, and is gunned down offscreen in the process. Before everything can be righted and Crystal Cove (as well as the world and universe) saved, most of the town is consumed by the “Evil Entity” and dies.

The bulk of the supernatural violence occurs in the second season, however, some victims of the man-in-mask capers do die (consumed by Cicada bugs or mauled to death offscreen by a parrot). Even Scooby’s girlfriend, Nova, is rendered comatose (then dies) in a Mufasa-inspired stampede scene. The exponentially-raised stakes require each episode to start with a recap, unheard of in the preceding incarnations, furthermore, it creates a tighter, more compelling narrative. In the second season, beloved characters like Angel Dynamite (inspired by Pam Grier and Blaxploitation heroines) sacrifices herself to save the gang, and drowns, while “Hot Dog Water” distracts the series’ villain, and is gunned down offscreen in the process. Before everything can be righted and Crystal Cove (as well as the world and universe) saved, most of the town is consumed by the “Evil Entity” and dies.

Furthermore, a larger and more diverse cast of characters bring life and authenticity (and even more intertextuality) to the Scooby-Doo Universe. Voice actors like Frank Welker and Mindy Cohn, who have voiced Fred (since the original run) and Velma for decades return for the eleventh incarnation, as well as film actors from the live-action films such as Matthew Lillard (Shaggy in the films and show) and Linda Cardellini (Velma in the films, “Hot Dog Water” in the show). Legends in the voice-acting industry like Clancy Brown, Mark Hamill, Jeffrey Combs, Tom Kenny, Maurice LaMarche (Vincent Van Ghoul), and Troy Baker also appear in numerous episodes as villains as well as extras.

The original Shaggy himself, Casey Kasem voices Colton Rogers, Shaggy’s father. Newcomers like Vivica A. Fox (Angel Dynamite), Patrick Warburton (Sheriff Sheriff Bronson Stone), Gary Cole (Mayor Jones, Fred’s father), horror legend Udo Kier (Professor Pericles), and comedian Lewis Black (Mr. E) play fundamental character and narrative parts in the show’s continuity. Other celebrity cameos (not actual guest stars like in other incarnations) like Ben McKenzie, Tia Carrere, Chris Hardwick, Beverly D’Angelo, speculative fiction writer Harlan Ellison (playing and voicing himself), George Takei, Jeffrey Tambor, and Florence Henderson contribute their voices to the vast sea of vocal talent, new and legendary.

Even the central gang is provided greater depth over the course of the show’s fifty-two episode run. Fred is still the blonde, competent leader, however he is extraordinarily dense (borderline dumb). He is a master at traps, all of which have names, histories, and configurations, and yet, about simple things like human emotion, romance, and common sense, he is lovably yet frustratingly idiotic. For example, in season 2 when Fred catches Velma red-handed working as a double agent for the nefarious Mr. E, he says this: “Velma: How long have you been standing there? Fred: Don’t try that. You know the concept of time confuses me.” Daphne is still danger-prone and pretty, but she is also very smart and savvy, and vulnerable to her own insecurities and needs (especially in regard to her feelings for Fred and the expectations of her parents). Velma is still the most intelligent of the group, but she hides her own insecurities about her appearance and future, and takes on a more sarcastic and sardonic tone, cracking most of the deadpan jokes. Her reason and logic is confronted by her family’s business – the commodification of Crystal Cove’s supposedly supernatural history. Shaggy and Scooby remain cowardly and constantly hungry, but are also brave when their friends are in danger, surprisingly intuitive, and struggle through a number of rough patches in their relationship due to secrets and jealousy.

Even the central gang is provided greater depth over the course of the show’s fifty-two episode run. Fred is still the blonde, competent leader, however he is extraordinarily dense (borderline dumb). He is a master at traps, all of which have names, histories, and configurations, and yet, about simple things like human emotion, romance, and common sense, he is lovably yet frustratingly idiotic. For example, in season 2 when Fred catches Velma red-handed working as a double agent for the nefarious Mr. E, he says this: “Velma: How long have you been standing there? Fred: Don’t try that. You know the concept of time confuses me.” Daphne is still danger-prone and pretty, but she is also very smart and savvy, and vulnerable to her own insecurities and needs (especially in regard to her feelings for Fred and the expectations of her parents). Velma is still the most intelligent of the group, but she hides her own insecurities about her appearance and future, and takes on a more sarcastic and sardonic tone, cracking most of the deadpan jokes. Her reason and logic is confronted by her family’s business – the commodification of Crystal Cove’s supposedly supernatural history. Shaggy and Scooby remain cowardly and constantly hungry, but are also brave when their friends are in danger, surprisingly intuitive, and struggle through a number of rough patches in their relationship due to secrets and jealousy.

The roster of baddies still includes shadowy figures, ghosts, and vampires, but also features slime mutants, gator people, gnomes, aliens, and graveyard ghouls, as well as creatures based in folklore and mythology such as the Slavic hag Baba Yaga, the mythical American Hodag, and the Persian sphinx-like manticore. Furthermore, almost every villain is inspired by some pre-existing material, like H.P. Hatecraft’s Char Gar Gothakon (based on H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu), the Dreamweaver (based on Labyrinth’s Jareth and Nightmare’s Freddy Krueger), Dead Justice (based on DC Comics supernatural western vigilante Jonah Hex), and the Nazi World War II-era Kriegstaffebots.

Heads and shoulders above the episodic villains is the general looming threat and mystery of both seasons, the first being – what happened to the original Mystery Incorporated, a group of teen sleuths in the 1970s who went missing from Crystal Cove? The second mystery is, why does Crystal Cove have so many crooks, men- or women-in-masks, and infinite mysteries? Is there perhaps a supernatural, magical, or a fantastical science-fiction cause at the core of the town’s mysteries?

There are too many references so here’s an image of a mind blow.

At the center of the show’s virtuosity is its interweaving of intertextual references, which as evidenced by multiple mentions above, are not only numerous but potentially innumerable. In the first season alone, there are visual, aural, and narrative allusions to films from the 1950s to the 1980s such as National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983), Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971), Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), E.T. (1982), Poltergeist (1982), and Indiana Jones (1981-9), to Vincent Price’s filmography, Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974) and Carrie (1976), The War of the Gargantuas (1966), James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984) and Aliens (1986), The Wild One (1951), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and John Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China (1986). More recent filmic references include The Silence of the Lambs (1991), Saw (2003), and the Twilight phenomenon and Stephenie Meyer (renamed the Dusk series in the show).

Furthermore, there are historical and contemporary references to other television shows like Beverly Hills, 90210 and The Flintstones as well as a few storylines resurrecting characters from other children’s cartoons like Sealab 2010, Moby Dick and Mighty Mightor, Jonny Quest, and Dynomutt, Dog Wonder. In fact, there is a whole episode (“Mystery Solvers Club State Finals, S1E14) which brings back the animation style of the original Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?, and features other Hanna-Barbera Creations, like The Funky Phantom, Speed Buggy, Jabberjaw, and Captain Caveman and the Teen Angels.

Furthermore, there are historical and contemporary references to other television shows like Beverly Hills, 90210 and The Flintstones as well as a few storylines resurrecting characters from other children’s cartoons like Sealab 2010, Moby Dick and Mighty Mightor, Jonny Quest, and Dynomutt, Dog Wonder. In fact, there is a whole episode (“Mystery Solvers Club State Finals, S1E14) which brings back the animation style of the original Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?, and features other Hanna-Barbera Creations, like The Funky Phantom, Speed Buggy, Jabberjaw, and Captain Caveman and the Teen Angels.

Beyond television and films, there are homages to fictional and actual figures, like H.P. Lovecraft (H.P Hatecraft), Harlan Ellison, Jonah Hex (Dead Justice), Andy Warhol (Andy Warsaw), and Che Guevara (Ernesto, the bearded, beret-wearing protester who calls everyone comrade). That last one is more surprising considering that when the original show premiered, Che had been recently executed, Cuba was the U.S.’s enemy, and the International Cold War reigned on.

Beyond television and films, there are homages to fictional and actual figures, like H.P. Lovecraft (H.P Hatecraft), Harlan Ellison, Jonah Hex (Dead Justice), Andy Warhol (Andy Warsaw), and Che Guevara (Ernesto, the bearded, beret-wearing protester who calls everyone comrade). That last one is more surprising considering that when the original show premiered, Che had been recently executed, Cuba was the U.S.’s enemy, and the International Cold War reigned on.

However, the intertextuality is truly innovative, because it not only appeals to adults, but creates a meta-humor, meaning an extratextual meaning (or joke) that can only be appreciated and enjoyed via knowledge of other texts and self-awareness.

The second season continues its intertextuality by referencing television shows, individual films and genres, franchises, comics books, and musical artists, as well as an unmistakably thorough homage to David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (1990-1), replete with a dancing little person who speaks backwards, a “Black Lodge” with checkered floors, red curtains, and odd statues, and an “Evil Entity” which has been infecting the town and its residents. (Here’s a lovely video of it). A child (age 6 to 12) may laugh at a female, badass soldier in “Dark Night of the Hunters” (S2E23), but won’t understand the joke, when she says that she went to “Fighter Weapons School” and her codename is “Ice Princess,” unless they’ve seen Top Gun (1986). The average child won’t even understand that the episode’s title is a reference to Charles Laughton’s fantasy-film noir The Night of the Hunter (1955). Therefore, this intertextuality plays between past and present pop culture, adding a layer of sophistication and intelligence, making a meta-humor.

In conclusion, Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? (1969-70) and Scooby-Doo, Mystery Incorporated (2010-3) reflect their contemporary role in the history and future of children’s animated content, their contextual attitude toward sexuality and violence (particularly, in children’s entertainment), and the prevalent typification of humor and entertainment of their respective time periods. While the original run is formulaic and static, presents controversial racial and sexual attitudes, and a primarily slapstick humor; and, the eleventh incarnation provides dynamic characters and scenarios, more mature content, and a meta-humor predicated on intertextuality, both are a part of the history of the Scooby-Doo franchise. Neither are footnotes in television history, but influential texts in the evolution of children’s animated content, which pave the way for new additions to the franchise, whether animated (Be Cool, Scooby-Doo!, 2015-present) or cinematic (S.C.O.O.B., 2020).

Hope you enjoyed this piece and my analysis of Scooby-Doo, Mystery Incorporated. Stay tuned for some new projects I’m developing. Thanks!

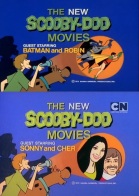

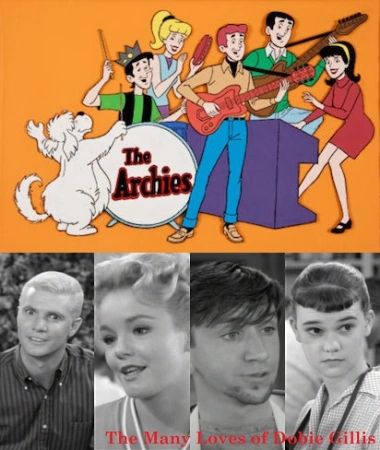

Instead of a half-hour mystery, each episode was an hour-long, and incorporates the still-present gimmick of the celebrity guest star. For twenty-four episodes, veteran comedy teams like the Three Stooges and Laurel and Hardy, musicians like Davy Jones, Cass Elliot, and Sonny and Cher, superheroes like Batman and Robin, other fictional TV characters like Josie and the Pussycats, Jeannie, and the Addams Family as well as other celebrities like the Harlem Globetrotters, cameoed during the gang’s mysteries (Burke & Burke 108).

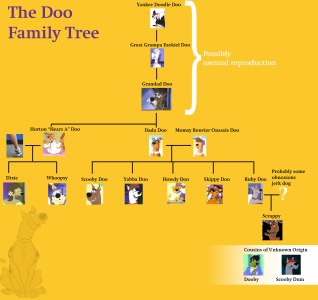

Instead of a half-hour mystery, each episode was an hour-long, and incorporates the still-present gimmick of the celebrity guest star. For twenty-four episodes, veteran comedy teams like the Three Stooges and Laurel and Hardy, musicians like Davy Jones, Cass Elliot, and Sonny and Cher, superheroes like Batman and Robin, other fictional TV characters like Josie and the Pussycats, Jeannie, and the Addams Family as well as other celebrities like the Harlem Globetrotters, cameoed during the gang’s mysteries (Burke & Burke 108). The third incarnation would not appear until three-years later at ABC, where Silverman had since moved (bringing Spears and Ruby back with him), with The Scooby-Doo Show (1976-8), Scooby-Doo and Scrappy-Doo (1979-80), Scooby-Doo and Scrappy-Doo (shorts; 1980-2), The New Scooby and Scrappy-Doo Show (1983-4), The 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo (1985), and A Pup Named Scooby-Doo (1988-91). Over the course of fifteen years, the franchise would retain the same foundation as well as the feature guest stars and collaborations (such as with Dynomutt and Scooby-Doo’s quirky “relatives”), however due to declining ratings, would reduce the focus on the gang as a whole, and shift towards Scooby and Shaggy, along with the newly invented Scrappy-Doo (Scooby’s puppy nephew).

The third incarnation would not appear until three-years later at ABC, where Silverman had since moved (bringing Spears and Ruby back with him), with The Scooby-Doo Show (1976-8), Scooby-Doo and Scrappy-Doo (1979-80), Scooby-Doo and Scrappy-Doo (shorts; 1980-2), The New Scooby and Scrappy-Doo Show (1983-4), The 13 Ghosts of Scooby-Doo (1985), and A Pup Named Scooby-Doo (1988-91). Over the course of fifteen years, the franchise would retain the same foundation as well as the feature guest stars and collaborations (such as with Dynomutt and Scooby-Doo’s quirky “relatives”), however due to declining ratings, would reduce the focus on the gang as a whole, and shift towards Scooby and Shaggy, along with the newly invented Scrappy-Doo (Scooby’s puppy nephew).

Retaining the formulaic episode format, the revival also returned to the man-in-mask routine that preceded the 1980s, ditched the laugh-track, upgraded the theme with a rendition from pop-punk band

Retaining the formulaic episode format, the revival also returned to the man-in-mask routine that preceded the 1980s, ditched the laugh-track, upgraded the theme with a rendition from pop-punk band

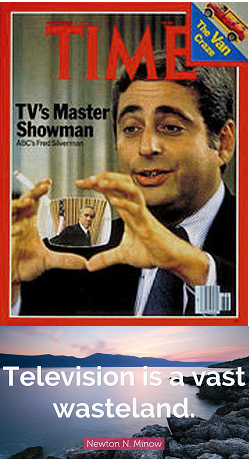

The show as conceived was an attempt by Silverman and CBS to “steer [the] network’s children’s programming away from the often-condemned violence of action and superhero shows [Adventures of Superman, Green Hornet] and toward humor” (“Scooby-Doo”). At the time, concerns came from parental watch groups, network executives, and the FCC’s Newton Minow, who had deemed the television landscape a “vast wasteland” in the early-1960s. However, at that point, the Saturday Morning lineup was not pervasive, with children’s content airing during the weekday and during primetime. With those scathing words, Minnow “set the terms of debate over the impact and meaning of television for decades to come. What is striking, then, is the centrality of children to Minow’s condemnation of television broadcasters” (Burke & Burke 13). While some solutions were the proliferation of educational programming, Silverman turned towards content and design revisions to create new, “safe” shows, reacting to social attitudes to race, sexuality, and violence in children’s media and the culture-at-large.

The show as conceived was an attempt by Silverman and CBS to “steer [the] network’s children’s programming away from the often-condemned violence of action and superhero shows [Adventures of Superman, Green Hornet] and toward humor” (“Scooby-Doo”). At the time, concerns came from parental watch groups, network executives, and the FCC’s Newton Minow, who had deemed the television landscape a “vast wasteland” in the early-1960s. However, at that point, the Saturday Morning lineup was not pervasive, with children’s content airing during the weekday and during primetime. With those scathing words, Minnow “set the terms of debate over the impact and meaning of television for decades to come. What is striking, then, is the centrality of children to Minow’s condemnation of television broadcasters” (Burke & Burke 13). While some solutions were the proliferation of educational programming, Silverman turned towards content and design revisions to create new, “safe” shows, reacting to social attitudes to race, sexuality, and violence in children’s media and the culture-at-large.

The gang would be participating in an innocuous activity, like a beach party or driving to a concert, and stumble upon some masked ghoul or ghost. Fred would call for an investigation, splitting the search parties between him and Daphne, and Velma, Shaggy, and Scooby, where they would search for clues and have a few run-ins with the “villain.” Next, Fred would conceive a Rube Goldeberg trap, if one of the gang, particularly Scooby, didn’t botch it. The “villain,” whether a vampire, werewolf, ghost, or robot, usually inhabited a spooky, haunted location like a castle on an island, a mansion in the country, or an abandoned beach or amusement park.

The gang would be participating in an innocuous activity, like a beach party or driving to a concert, and stumble upon some masked ghoul or ghost. Fred would call for an investigation, splitting the search parties between him and Daphne, and Velma, Shaggy, and Scooby, where they would search for clues and have a few run-ins with the “villain.” Next, Fred would conceive a Rube Goldeberg trap, if one of the gang, particularly Scooby, didn’t botch it. The “villain,” whether a vampire, werewolf, ghost, or robot, usually inhabited a spooky, haunted location like a castle on an island, a mansion in the country, or an abandoned beach or amusement park. He (or she, although only in “Foul Play in Funland” [S1E8]) is unmasked, and their motive revealed to be the pursuit of treasure or wealth, revenge, or an attempt to cover up some larger crime (i.e. forgery, theft, counterfeiting). The deputy or sheriff would inquire how they solved such an unsolvable crime, praise them, and escort the villain away. Scooby would perform some final gag, and end the episode with a “Scooby-dooby-doo.” Other signatures include a laugh track, a visit to a malt shop, the essential early-1970s outfits replete with ascots, turtlenecks, and bell-bottom pants, and character catchphrases like Velma’s “Jinkies” or Shaggy’s “Zoinks.”

He (or she, although only in “Foul Play in Funland” [S1E8]) is unmasked, and their motive revealed to be the pursuit of treasure or wealth, revenge, or an attempt to cover up some larger crime (i.e. forgery, theft, counterfeiting). The deputy or sheriff would inquire how they solved such an unsolvable crime, praise them, and escort the villain away. Scooby would perform some final gag, and end the episode with a “Scooby-dooby-doo.” Other signatures include a laugh track, a visit to a malt shop, the essential early-1970s outfits replete with ascots, turtlenecks, and bell-bottom pants, and character catchphrases like Velma’s “Jinkies” or Shaggy’s “Zoinks.” Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? lays the foundation for the next eleven incarnations, however, the original run is incredibly formulaic and static, includes segments that are racially and culturally insensitive and rely on temporally-contextual humor (which don’t age well), and possesses none of the variations that will elevate later versions of the property as well as animated content in general. The episode construction described above does not vary in the first run’s twenty-five episodes, and illustrates simultaneously TV’s camp craze during the 1960s, and Silverman’s deep appreciation for the Universal Horror films (Cronin), exemplified in the typical choice of weekly villains (mummy, Frankenstein, vampire, zombie, witch, etc.).

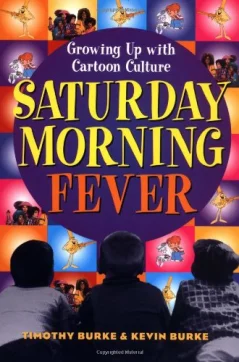

Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? lays the foundation for the next eleven incarnations, however, the original run is incredibly formulaic and static, includes segments that are racially and culturally insensitive and rely on temporally-contextual humor (which don’t age well), and possesses none of the variations that will elevate later versions of the property as well as animated content in general. The episode construction described above does not vary in the first run’s twenty-five episodes, and illustrates simultaneously TV’s camp craze during the 1960s, and Silverman’s deep appreciation for the Universal Horror films (Cronin), exemplified in the typical choice of weekly villains (mummy, Frankenstein, vampire, zombie, witch, etc.). Each episode presented a “new” villain, low stakes, no overarching plot or character arc, and no attempt at a backstory for either their one-dimensional protagonists or zero-dimensional antagonists. In the decades following, the show’s narrative superficiality and flaws in logic would become substantial, some of which are proposed by one of the few notable examinations of the show, in 1999’s Saturday Morning Fever (Burke & Burke, 105-6): How old is the gang? Do they go to school? How do they afford to travel across the country to solve crimes? Do they get paid? Where are their parents? Is this dog really talking or is Shaggy experiencing “reefer madness?” Are Fred and Daphne a couple, and what do they really do when they all split up? Is Velma a lesbian? How close are Shaggy and Scooby, and are they potheads? Why are there so many mysteries? Burning questions, all of them, but none of which are answered in the first incarnation.

Each episode presented a “new” villain, low stakes, no overarching plot or character arc, and no attempt at a backstory for either their one-dimensional protagonists or zero-dimensional antagonists. In the decades following, the show’s narrative superficiality and flaws in logic would become substantial, some of which are proposed by one of the few notable examinations of the show, in 1999’s Saturday Morning Fever (Burke & Burke, 105-6): How old is the gang? Do they go to school? How do they afford to travel across the country to solve crimes? Do they get paid? Where are their parents? Is this dog really talking or is Shaggy experiencing “reefer madness?” Are Fred and Daphne a couple, and what do they really do when they all split up? Is Velma a lesbian? How close are Shaggy and Scooby, and are they potheads? Why are there so many mysteries? Burning questions, all of them, but none of which are answered in the first incarnation.