Dear Reader:

Friday has at last come and with it, Crazed Fruit! Before I jump into the brief analysis, I want to 1) discuss my experience watching this film as a spectator and 2) provide a rough sketch of the film’s narrative. [If you have not seen the film, but would like to, this eighty-six minute feature is not available for streaming on iTunes or Amazon, but is accessible on DVD from Netflix and may be streaming on Hulu. For those of a particular thriftiness, you may potentially find this film elsewhere and procure it by alternative means.] Here is a lovely and adorable English-subtitled trailer. Also, for a historical and cultural context, make sure you already perused yesterday’s post (“Read Me Tender”).

When I first viewed this film, I experienced a variety of emotions –

- Wow, this film is shot wonderfully, totally French New Wave

- I hate these characters, they are such self-absorbed a**holes

- Oh my god, what is happening

- Bros, am I right?

- This ending is insanity

- Crazed Fruit is freaking brilliant

- *slow claps in mind because you’re in a crowded room*

The film is at once breathtaking, bold, and bonkers to watch, and for the record, I highly recommend it. To the synopsis . . .

>>>>ATTENTION – TO AVOID SYNOPSIS, SCROLL UNTIL YOU SEE THE PICTURE.<<<<

The elder Natsu and his “Sun Tribe” are spending their summer in a middle-class coastal community – drinking, partying, and using and abusing a range of women. Enter the younger Haru, Natsu’s brother, unitiated into the Tribe. While Haru is naive and optimistic, Natsu and his gang (led by the biracial Frank) are cynical and nihilistic, in general philosophical rebellion against their parent’s and society’s expectations of and for them. Basically, they got the ennui real bad. Meanwhile, Haru keeps on encountering a beautiful woman, named Eri, and eventually starts a relationship with her, punctuated by scenes of extreme adolescent sexual tension. Upon meeting Eri at a party, Natsu finds he does not trust her seemingly innocent facade (although he is also attracted to her) and discovers her dark secret – she is married to an older American businessman and habitually has flings while he’s away, which is often. Threatening her to stay away from his brother, he engages in sexual blackmail: I won’t tell my brother you’re married if you also sleep with me, which she does. However, Eri sees Haru as the redemption of her younger, freer self and eventually they consummate the relationship, but Natsu has become increasingly obsessed with Eri. To win her away from his brother, Natsu “kidnaps” Eri on his boat (revealing the affair to Haru in the process). In the end, the jealousy, obsession and betrayal is too much – as relayed by the surprising voice of reason, Frank – and Haru runs down both Eri and his brother Natsu with his boat, murdering them in cold blood. THE END. H.A.G.S.

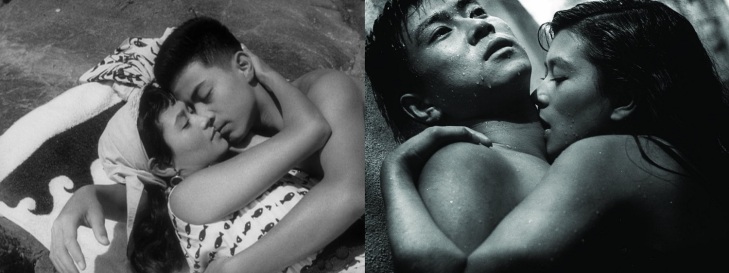

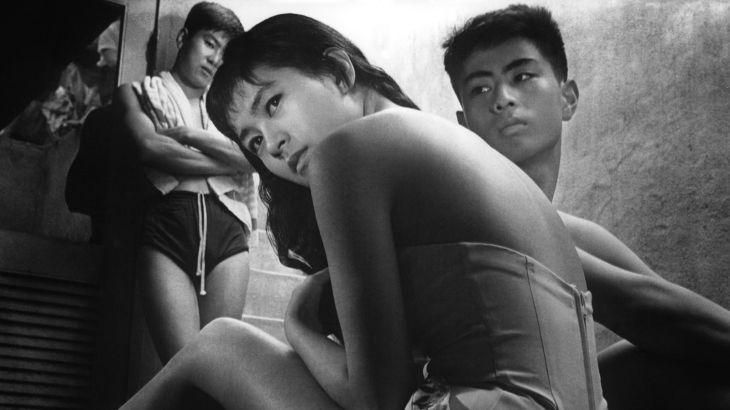

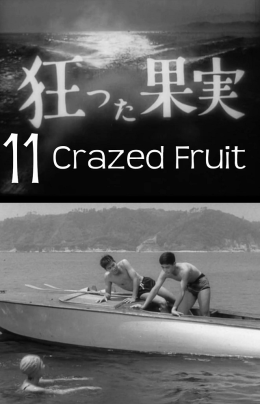

From left to right: Yujiro Ishihara as NATSU, Mie Kitehara as ERI, and Masahiko Tsugawa as Natsu’s younger brother HARU.

Crazed Fruit (writ. Shintaro Ishihara) was released in 1956 by Nikkatsu, the oldest major movie studio in Japan. Featuring the studio’s line-up of new, young stars, including Yujiro Ishihara, Masahiko Tsugawa, Mie Kitahara, and Masumi Okada, the film follows the destructive love triangle between two brothers, the older Natsu (Y. Ishihara) and younger Haru (Tsugawa), and a mysterious, beautiful young woman named Eri (Kitahara). Paired with (S.) Ishihara’s Season of the Sun (dir. Takumi Furukawa, 1956), Crazed Fruit is one of the inaugural films of the short-lived Sun Tribe movement (taiyo-zoku eiga), an artistic subculture which emerged in postwar Japan of the 1950s and 1960s, at the start of the Japanese New Wave. Utilizing unconventional stylistic techniques and controversial subject matter, Crazed Fruit explores themes resonant in contemporary Japan, specifically the intersection of conflicts between cultures, generations, and philosophical ideologies.

Note: Sorry, reader, more history – film history specifically – is required.

During World War II and the immediate postwar years, the Nikkatsu studio was reluctantly forced to merge with two weaker companies (Shinkō Kinema and Daiko) under Daiei Film, which resulted in the undervalued Nikkatsu ceasing actual film production.

In the postwar expansion of the nation’s film industry, Nikkatsu constructed a new production studio, with production officially re-commencing in 1954, marked by a creative and economic resurgence of the veteran studio (2007: Standish, 142-4). Consequently, due to the war and the merger, Nikkatsu was struggling to compete with the Big Four studios (Toho, Shochiku, Toei, and Daiei), and had essentially lost its individual identity. With the provocative Sun Tribe films, the studio, like the film’s characters and its corresponding subculture, is trying to forge a new identity in the postwar era, between generations, cultures, and ideologies.

In the postwar expansion of the nation’s film industry, Nikkatsu constructed a new production studio, with production officially re-commencing in 1954, marked by a creative and economic resurgence of the veteran studio (2007: Standish, 142-4). Consequently, due to the war and the merger, Nikkatsu was struggling to compete with the Big Four studios (Toho, Shochiku, Toei, and Daiei), and had essentially lost its individual identity. With the provocative Sun Tribe films, the studio, like the film’s characters and its corresponding subculture, is trying to forge a new identity in the postwar era, between generations, cultures, and ideologies.

Running concurrently with the French New Wave, the beginnings of the Japanese New Wave are visible in the visual style of Crazed Fruit. For those unfamiliar, the Japanese New Wave, very roughly, was a group of semi-connected filmmakers and films, originating from a trend towards creative experimentation and reflection in the 1960s. In direct confrontation of Classical filmmaking and filmmakers, these more avant-garde artists produced compelling and daring works, pushing formal (cinematography, editing), narrative (linearity, structure), and thematic boundaries, tackling taboo subject matter and navigating the trauma and aftermath of World War II on the Japanese psyche.

Running concurrently with the French New Wave, the beginnings of the Japanese New Wave are visible in the visual style of Crazed Fruit. For those unfamiliar, the Japanese New Wave, very roughly, was a group of semi-connected filmmakers and films, originating from a trend towards creative experimentation and reflection in the 1960s. In direct confrontation of Classical filmmaking and filmmakers, these more avant-garde artists produced compelling and daring works, pushing formal (cinematography, editing), narrative (linearity, structure), and thematic boundaries, tackling taboo subject matter and navigating the trauma and aftermath of World War II on the Japanese psyche.

In the opening of Crazed Fruit, cinematographer Shigeyoshi Mine utilizes dolly and tracking shots and extreme close-ups, shifting from the blistering natural sunlight of the day scenes to the shadowy, humid darkness of the night scenes, to create a paradoxical aesthetic of highly-stylized cinéma vérité. Mine and editor Masanori Tsujii smash from fast-paced, kinetic editing with equally frenetic in-frame action (e.g. running, jumping, speed boating) to longer, languid shots of contemplation and internal conflict (e.g. laying in bed, on the shore, looking off-distance). Unlike other film genres or earlier Japanese cinema, Crazed Fruit focuses on directionless movement – speed and urgency without any tangible direction or destination – by doing away with older traditions of the consistently static camera, a reminder of the country’s gradual ambivalence and acceptance of new technology (from sound to color to widescreen). Furthermore, the subject matter, including the rejection of parental authority, adventurous, pre-marital sex, and images of apocalyptic and seductive violence, attempts to capture the painful and inescapable present, rather than providing a historical period or familiar structure through which to negotiate contemporary social anxieties.

In the opening of Crazed Fruit, cinematographer Shigeyoshi Mine utilizes dolly and tracking shots and extreme close-ups, shifting from the blistering natural sunlight of the day scenes to the shadowy, humid darkness of the night scenes, to create a paradoxical aesthetic of highly-stylized cinéma vérité. Mine and editor Masanori Tsujii smash from fast-paced, kinetic editing with equally frenetic in-frame action (e.g. running, jumping, speed boating) to longer, languid shots of contemplation and internal conflict (e.g. laying in bed, on the shore, looking off-distance). Unlike other film genres or earlier Japanese cinema, Crazed Fruit focuses on directionless movement – speed and urgency without any tangible direction or destination – by doing away with older traditions of the consistently static camera, a reminder of the country’s gradual ambivalence and acceptance of new technology (from sound to color to widescreen). Furthermore, the subject matter, including the rejection of parental authority, adventurous, pre-marital sex, and images of apocalyptic and seductive violence, attempts to capture the painful and inescapable present, rather than providing a historical period or familiar structure through which to negotiate contemporary social anxieties.

The primary conflicts of Crazed Fruit occur on three levels – between older and younger generations, Western and Japanese culture, and pre-existing and emerging ideological expectations. The aforementioned stylistic differences are a visual representation of the shifts between different generations of studios, directors, and spectators.

The film’s characters, mostly youths, are placed in constant opposition to their parent’s generation. For example, in the house of Natsu and Haru, their mother wears a kimono and the dwelling’s architecture leans towards the traditional. In contrast, none of the younger girls in the film ever wears a kimono, and in fact, are often shown in various states of undress and engaging in flirtatious or overtly sexual behavior. Parents, in general, are noticeably absent from the lives of most of the characters, such as Frank (Okada), the half-white, half-Japanese “leader” of the Sun Tribe, whose parents are divorced and mostly missing throughout the film. The expectations of the older generation are ever-present in the Tribe’s rebellion: in an early scene, the thesis of the Tribe is expounded upon for the newer Haru, displayed in successive quick shots, cuts chopping at a breakneck speed, extreme and skewed close-ups, with overlapping dialogue. Blending fatalism and existential ennui, Crazed Fruit affects a nihilistic interpretation of the later-released Gidget (dir. Paul Wendkos, 1959). The Tribe’s apathetic declaration decries the conventional expectations of Japanese youth – school, work, marriage, and family – and, instead, the Tribe experiences an existential malaise, punctuated by sex, violence, adrenaline, and fleeting gratification in material and physical pleasures.

I wish I could find a clip, but here is the transcript for the Sun Tribe speech:

Natsu takes Haru to Frank’s house (parents absent) and the boys lay into Haru about his traditional view of the world. The metaphor for fish is constant, ugly women are “fish bait” while beautiful women are “big catches” and “mermaids;” and the ideals of the older generation are comparable to fragile tropical fish.

Boys #1 and #2: We’re just bored.

Haru: Then find something to do.

Boy #3: Like what?

Natsu: “Something” isn’t so easy to find. Intellectual high-minded talk isn’t worth a damn. The words may be pretty, but the ideas are as flimsy as those fish. Look at ’em. They’re fine now, but let the water get dirty or cold and they go belly-up.

Haru: Stop.

Natsu (extreme-close tilted angle): Fancy words and old ways don’t cut it now. We need something with a fresh nip to it.

Boy #4 (extreme close-up): Listen to your professors, always spouting the same drivel. It was okay before, but it’s outdated nonsense now.

Boy #5 (extreme close-up): You know Tachikawa in economics? He said we were future captains of industry. You’d think he was narrating a silent movie. Chasing rainbows, with the Soviets and Red China next door.

Boy #4 (extreme close-up): And he’s considered a leading thinker.

Natsu (extreme-close tilted angle): Look what the older generation tries to sell us. You find anything exciting in that?

Boy #4 (extreme close-up): I’d given up trying. We’ll find our own way to live.

Haru: And this is it? Aimlessly killing time?

Natsu (extreme-close tilted angle from opposite side): We do the best we can.

Haru: It’s all just a bunch of bullshit. You guys have no idea what you want to do. That’s why you’re always so bored. They call people like you the Sun Tribe. I’m not gonna live like that.

Natsu (extreme-close tilted angle): What do you say we should do?

Haru: Well . . .

Natsu (extreme-close tilted angle): There’s nothing to throw ourselves into even if we wanted.

Girl (extreme-close tilted angle): We live in boring times.

Natsu (extreme-close tilted angle): Exactly. So we make boredom our credo. Eventually something will come of it.

Girl (extreme close-up): Exactly. Anybody hungry?

On the line between childhood and adulthood, the adolescents also straddle the fading divide between traditional Japanese culture and the economic and cultural domination of American products.

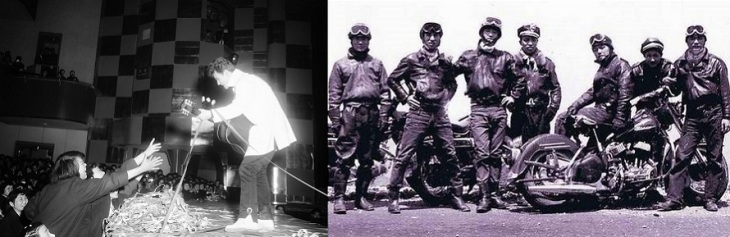

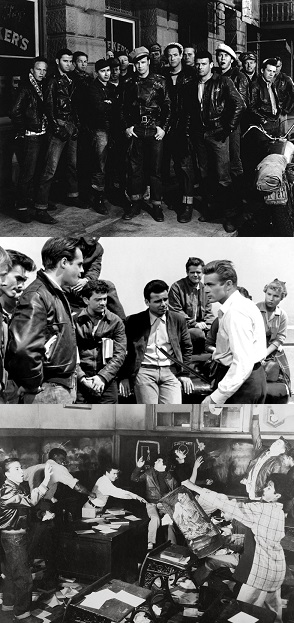

Crazed Fruit features many visual, narrative, and thematic allusions to similar expressions of youth culture occurring contemporaneously in Hollywood cinema, exemplified in The Wild One (dir. László Benedek, 1953), Rebel without a Cause (dir. Nicholas Ray, 1955), and The Blackboard Jungle (dir. Richard Brooks, 1955). Both film movements focus on the immediate present, youth protagonists, and the volatile and rebellious interiority of the postwar generation. In a more ominous connection, James Dean died in a fatal car accident, in 1955, at the age of 24, while speedily driving down a California highway, a comparable message is found in the ending of Crazed Fruit, as Haru violently runs down his brother and Eri with a speedboat – live fast and die young. The presence of American and Western culture is pervasive throughout the film. More subtle examples include the visibility of English-language signs and brief uses of English by the characters, as well as the use of American jazz music in the background and the Elvis Presley-inspired musical persona of Natsu. However, more prominently, Crazed Fruit displays an evolving Japanese modernity equally predicated on materialism and consumerism, amassing houses, cars, summer getaways, and plenty of free-flowing money to give their reckless and emboldened youths, who don requisite Hawaiian shirts and sports jackets. Furthermore, the appearance of interracial relationships, such as between Eri and her unnamed middle-aged American husband (Harold Conway), also visualize American domination over Japan, through military occupation, cultural invasion, and additionally, via Japanese women.

In conclusion, Crazed Fruit cinematically manifests the generational, cultural, and ideological conflicts of the postwar youth generation, exemplified at-large in the brief, provocative, and influential Sun Tribe movement.

That ends this week’s post, but please return for next Friday’s analysis of Masayuki Suo’s international cinematic hit Shall We Dance? (1996). And no, not the one with Richard Gere doing the tango with J. Lo in a dark, deserted ballroom, but the original, before the uber-masculine white collar corporate culture of America got its remaking-dance shoes stuck in its mouth.

Works Cited

- Blackboard Jungle, The. Dir. Richard Brooks. Perf. Glenn Ford, Sidney Poitier, Vic Morrow, Anne Francis and Louis Calhern. MGM, 1955. Film.

- Crazed Fruit. Dir. Kō Nakahira. Perf. Yujiro Ishihara, Mie Kitahara, Masahiko Tsugawa and Masumi Okada. Nikkatsu, 1956. Film.

- Gidget. Dir. Paul Wendkos. Perf. Sandra Dee, James Darren and Cliff Robertson. Columbia, 1959. Film.

- Rebel without a Cause. Dir. Nicholas Ray. Perf. James Dean, Natalie Wood and Sal Mineo. Warner Bros., 1955. Film.

- Standish, Isolde. “Cinema and the State.” A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film. NY: Continuum International Publishing, 2006, pp. 142-4. Print

- Wild One, The. Dir. László Benedek. Perf. Marlon Brando, Mary Murphy and Robert Keith. Columbia, 1953. Film.